The Steal 011

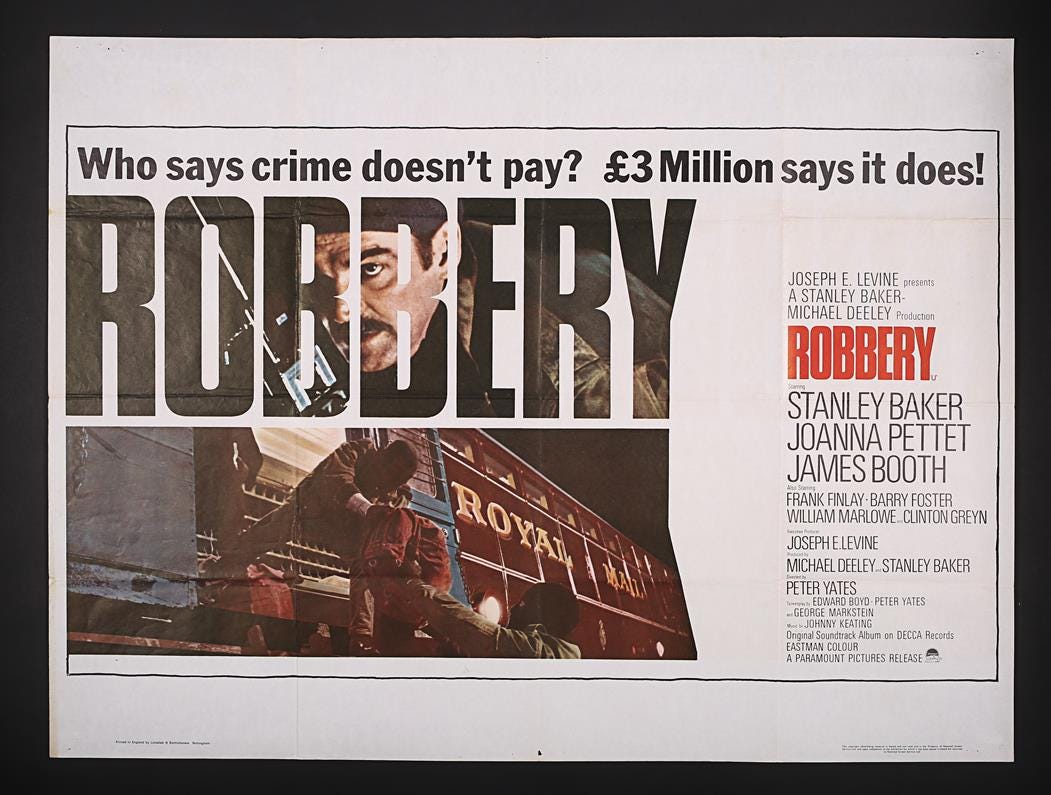

Robbery (1967)

Yeah, we’re not talking about THE TOWN (2010) yet. In fact we’re having nun of it.

But you know heist music is its own thing, right? Go ask Rob to tell you about it (take a thermos and a sandwich - he has opinions), but what about music about heists?

There’s a fair few ballads of course, bank robbers of old being a tad romantic, love swept and doomed rather than say the burly sweary blokes pursued by The Sweeney even if their shooters were all sexy and gold plated.

But it’s kind of a lost art now right?

When was the last great song about a caper?

You could probably assemble one. A William S. Burroughs style cut-up aided and abetted by AI with a little bit of “I first produced my pistol And then produced my rapier I said “Stand o’er and deliver Or the Devil, he may take ya” here crossed with a little “Now one brave man-he tried to take ‘em alone They left him lying in a pool of blood And laughed about it all the way home” there.

You know, a little bit gonzo

And we can be pretty divisive with our opinions in the newsletter.

What do you mean you think RONIN (1998) is a piece of crap?

Hang on, you think DeNiro in HEAT (1995) is what now?

How many dogs does it take to rob a bank anyway? Six dobermans and a bulldog or a full colour palette with one non tipper?

Why do you watch so many OLD things when Marky Wahlberg makes a new movie every month?

shudder

But, if there’s one thing we can all agree on it’s that the best song about a bank robbery going wrong in Canada because of an unexpected gaggle of nuns is this one:

Hit the organ solo.

This is The Steal.

Rob pulls on his balaclava and gets behind the wheel of his Jag to commit ROBBERY (1967).

“Money breeds money.”

“Mine must be on the pill.”

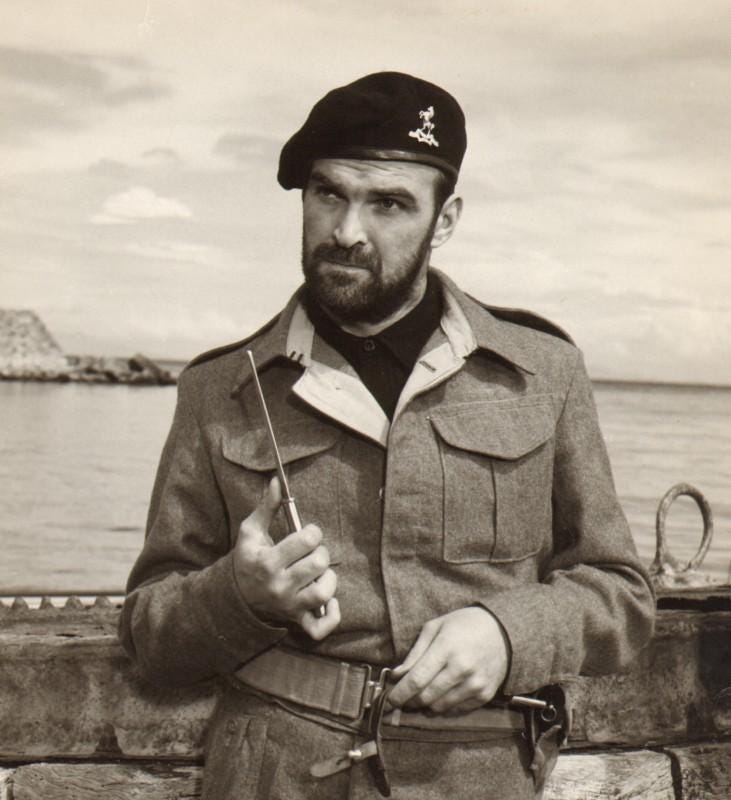

ROBBERY is the product of two very different men. In one corner you’ve got Stanley Baker, the son of a one-legged Welsh coal miner and a self-confessed ‘wild kid’ who dreamt of escaping the mines via the boxing ring. And in the other corner is Michael Deeley, who was sent to boarding school at the age of six and who fell into the film world because he needed a job before going to Oxford and his mum was PA to Douglas Fairbanks Jr.

Somehow these two men not only found each other, they made one of the most influential and stylish British heist films of the 1960s.

In 1963 the Great Train Robbery had seized the imagination of the country, thanks to the sheer audacity of the job and the fact that most of the £2.6 million (around £65-70 million in today’s money) that was lifted from the Glasgow-to-London Royal Mail train was never found.

In the same year, Michael Deeley was trying to graduate from the cutting room to the producer’s chair with SANDY THE RELUCTANT NUDIST (no explanation needed) and the ONE WAY PENDULUM (1964), an absurd comedy in which Jonathan Miller teaches weighing machines how to sing.

ONE WAY PENDULUM was “not widely seen” but it did mark the partnership of Deeley and a young, ambitious director named Peter Yates. After ONE WAY PENDULUM flopped, Yates went back to directing episodes of THE SAINT, but he must have seen something in Deeley, because when the producer came back a year later holding the rights to a paperback book purporting to be ‘The Real Story of the Great Train Robbery’ Yates signed on as director.

With mainly skin flicks and singing scales on their CVs, Deeley and Yates were struggling to get funding for their train caper, so Deeley went to see a man who’d started out playing hardened crooks and even harder cops in medium budget crime fare, before landing parts in big Hollywood films like GUNS OF NAVARONE (1961) and THE ANGRY HILLS (1959).

Stanley Baker had, like his mate Richard Burton, left the hills of his homeland far behind. But, unlike Burton, Baker was too rough around the edges to land many pretty boy romance roles. He needed a safety net and he found one in producing. If Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas could do it, then why not the 35-year-old miner’s son from Glamorgan?

Stan’s first effort as both star and producer was a little picture called ZULU (1964).

Not a bad start.

A couple of years later, when Deeley knocked on his door with his Great Train Robbery script in his hand, Baker saw the potential in both the script and the man and the pair set up a company called Oakhurst Productions. Their first film would be ROBBERY, in which Baker would star as the gang’s (fictional) mastermind, Paul Clifton.

To avoid legal problems, they decided the 25-minute robbery sequence would be based on actual court evidence, but pretty much everything else would be pure invention. So you shouldn’t come to ROBBERY expecting a documentary. Instead you should come expecting something that sometimes feels a lot like a documentary, sometimes like a highly stylised 60s cigarette ad, and at other times like those two things having a fumble by the bins out the back of a jazz club.

Exhibit A: ROBBERY’s opening sequence in which Baker’s crew gasses a diamond courier on a London street, bundles him into a stolen ambulance, and extracts a briefcase containing the jewels. It's all Hitchcockian suspense, rooftop pans and patient, composed dread… Right up to the point when the cops spot them during a vehicle change and a car chase erupts through the West End.

Yates shoots the whole chase guerrilla-style, the silver Jag careering through London streets like a rabid urban fox. But even though it sometimes feels like the camera is not going to make it out of there alive, the entire thing is an exercise in frenetic panache. The bit where a bobby smashes the windscreen of the getaway car as it nearly mows him down before the driver punches out the remaining glass, is gasp-inducing no matter how many times you see it.

If you know anything about ROBBERY then it’s probably the fact that Steve McQueen saw this sequence and hired Yates to direct BULLITT (1968), a film which produced the ‘most famous car chase in cinema’. But I’m going to say the chase in ROBBERY is better. There’s a freewheeling recklessness to it that Hollywood can’t quite deliver (Exhibit B: The gang nearly mows down a lollipop man and a whole procession of schoolchildren, and they look like they’re having a whale of a time doing it).

After that extraordinary opener the film does shift down a gear. And if there’s a reason ROBBERY has been neglected a little over the years, it’s because that car chase is too good. The film just can’t sustain that pace, especially as we then have to go into planning mode; getting the gang together and studying blueprints and train timetables etc.

That’s not to say the rest of the film isn’t packed with brilliant, memorable moments. There’s ducking-and-weaving, grab-what-you-can scenes like the one filmed at Leyton Orient’s Brisbane Road ground, where the gang gets together to argue about money during an actual Third Division match against Swindon Town. And then there’s the noirish, high-gloss segments like the glimpse we get into Clifton’s domestic life, where he argues with his impossibly glamorous wife (Joanna Pettet) in his beautiful home.

I mean, just look at this shot:

There’s also a police line-up scene to end all police line up scenes and a cracking prison break. And then there’s the robbery itself which unfolds with the patience of a procedural, all changed signals, quiet, nervous waiting and cash loaded methodically into a truck before the allotted time runs out. Douglas Slocombe’s camera (he’d go on to shoot RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK) renders all of this with gorgeous precision, but the content is deliberately unglamorous and, at times, necessarily brutal. These aren’t gentlemen thieves after all. They’re thugs in balaclavas.

Throughout this murky mix of visual bravado, gritty realism and heightening stakes the film keeps stopping for cups of tea, cigarette breaks and the odd sandwich (a real doorstepper of a cheese butty gets eaten while the loot is counted). “This is Mr Whatley, Post Office Security,” announces Glynn Edwards’ police chief in the immediate aftermath of the robbery. “Not the happiest man you’ll meet this morning.”

That’s the British heist film for you: world-class style punctuated by the kind of deadpan tone you’d expect from a regional train station announcer.

The supporting cast is stacked with the kind of British character actors who can make tea drinking feel almost Shakespearean. Barry Foster and George Sewell share a moment where they burn a fiver to light their fags. Frank Finlay plays a mousy embezzler with a touch of the wobbles. James Booth does his best miserable-but-tenacious bloodhound impression as the cop who won’t let go. And there’s even a very young Robert Powell showing up as a train conductor.

ROBBERY did good business in Britain and got Yates to Hollywood, but then it slipped into obscurity for decades, available only on a lousy VHS, while its flashier sibling THE ITALIAN JOB (1969) (also produced through Baker’s Oakhurst Productions) became a national treasure.

But I would argue that ROBBERY was, well… Robbed.

Before ROBBERY, the British crime genre was crowded with kitchen-sink grimness or Ealing whimsy. Yates proved you could have both the grit and the glamour without either cancelling the other out. Without ROBBERY there is no GET CARTER (1971) and no THE LONG GOOD FRIDAY (1980).

Just like Stanley Baker had shown that a working-class lad from the valleys can become a serious Hollywood leading man, ROBBERY tried to show that British crime films, just like a lot of British criminals, could be quiet and charming one minute and loud and dangerous the next. For that it was punished. Maybe it’s time it got released for good behaviour.

The Steal’s Poster of the Week

Want us to take a dive on a particular heist movie? Leave us a suggestion or two in the comments and feel free to let us know how we’re doing. We’d love to build THE STEAL around our readership, so come on board and help us course correct as we go.

Heist News

If your’e in New York then, well done on voting in Mamdani, now can you do something about the guy in the White House? And also, you might want to book tickets to see The Bear alumni, Jon Bernthal and Ebon Moss-Bachrach, in the broadway version of Dog Day Afternoon, which opens on March 10.

We can’t let a TV programme called Steal go by without a mention, even if the trailer does look terribly flat and dull. It’s out on Prime now and Lucy Mangan gives it four stars in the Guardian, but then Mangan’s record is… patchy (she gave the Leo Woodall-starring thriller Prime Target four stars too - and that was bloody awful).

Talking of Woodall he’s starring in new heist film TUNE as “as a gifted young piano tuner whose heightened sense of hearing draws the attention of criminals”. But also: Dustin Hoffman! Here’s the trailer so you can draw your own conclusions:

Next Issue

Did you know TISWAS was an acronym for Today Is Saturday: Watch and Smile? Did you also know that Ernest Borgnine, Lee Marvin and a huge fuckoff pitchfork pop up in the 1955 caper VIOLENT SATURDAY? Mike spills his guts all about it next issue.

Thanks for reading. Thanks for subscribing. Thanks for sharing. Once the heat dies down we’ll see you at the prearranged location to split the take. What could possibly go wrong?

Great piece! Have a feeling I’ve seen this many years ago but am going to seek it out for a re-watch. Stanley Baker is eminently watchable (Hell Drivers and Hell Is a City are brilliant!).

Brilliant case for giving ROBBERY its due as a stylstic bridge between earlier British crime films and the grittier 70s era. That bit about how Baker proved working-class actors could anchor serious films while ROBBERY showed the genre could mix grit with glamour without contradiction really lands. I remember seeing a VHS copy at a mate's place in the 90s and the opening chase scene was almost incomprehensible on that quality, but stil managed to feel urgent.