The Steal 010

High Sierra (1941)

What would you do if I asked you to hum an action movie? You might have some idea but it’s tough to hum Hans Zimmer doing unspeakable things to a French horn. What about a rom-com? A western? A war movie? You can’t do it. That’s because so much genre music tends toward the functional but forgettable. You feel it in while you’re in your seat, but you’ve probably forgotten it by the car park.

But you can probably hum a heist movie.

The genre has a sound so specific, so immediately recognisable, it’s almost like it’s always been there (especially when you consider that the most celebrated heist sequence in cinema history unfolds in complete silence) .

So where does the sound come from?

I’m going to pin it on the cartoon cat.

When Henry Mancini wrote the theme for THE PINK PANTHER (1963), he wasn’t so much writing a score, as much as summoning it from the ether. That creeping vibraphone, that tenor sax sidling in like a dodgy uncle at a party… It tells you everything you need to know, i.e. Someone is up to no good and that someone is going to have a great time doing it. With THE PINK PANTHER Mancini gave the genre its swagger.

Three years later, Lalo Schifrin (RIP) lit its fuse. The MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE theme, took Mancini’s cool and slathered it in urgency. With that 5/4 time signature pushing you forward whether you like it or not, Schifrin taught caper flicks how to run.

A couple of years later Michel Legrand’s score for THE THOMAS CROWN AFFAIR (1968) brought champagne flutes to the hippy happening. The Windmills of Your Mind introduces trippy elegance, slows things down a bit (Crown doesn’t need to run, he has people for that), and falls in love with the girl as well as its own cleverness.

And then, just a year later, Quincy Jones crashes the whole affair with THE ITALIAN JOB (1969), turning the cocktail party into a stag do, only with better cars. The swing is still there, but now it’s a knees up in a pub. A bit daft and (a bit like Spaghetti Bolognese) way more British than Italian.

Four scores in six years. That’s all it took to give heist movies their indelible sonic fingerprint.

By the time Steven Soderbergh conjured up the ghosts of the Rat Pack in OCEAN’S ELEVEN (2001), David Holmes knew exactly which threads he needed to pull as he filtered Mancini’s cool through four decades of jazz-inflected, larcenous lounge lizards.

The heist movie found its sound by stealing from the best.

Grab a coffee for this one as Sizemore gets a little indulgent and teary-eyed over one of the all-time classics, HIGH SIERRA (1941).

“Of all the 14 karat saps... starting out on a caper with a woman and a dog.”

Forget for a moment THE MALTESE FALCON (1941), CASABLANCA (1942) and everything that followed to cement Humphrey Bogart as a movie star and a twentieth century cultural icon. His leap from studio workhorse to defining roles took less than nine months. This gritty little crime caper wrapped late September 1940 while FALCON began shooting June 9th, 1941.

Bogart’s career moved so fast it gives you whiplash just thinking about it. HIGH SIERRA (1941) was the catapult.

Before he was a leading man, Bogart was a trigger-happy supporting act - the guy the studios hired to die before the third act. Even in his smallest or most miscast roles - DEAD END (1937) and THE RETURN OF DR. X (1939) - he stood out. Grinding through seven movies a year, every scrap of screen time added up. Hollywood and audiences alike began to take notice of this hard-boiled New Yorker who made stealing scenes look easy.

HIGH SIERRA, based on the novel of the same name, was a hot property. Warner Bros. thought they were buying the latest in a hit run of tough-guy, tommy-gun movies, but it’s not really a gangster picture at all. It’s just dressed like one.

The story of aging outlaw Roy Earle - sprung from prison for one last job and slowly realising he’s run out of road - plays closer to a western than a crime caper, but the studio focussed on the fedoras and machine guns when it came to casting.

For Earle, they wanted Paul Muni, the original Scarface (1932). But Muni had a grudge against John Huston who was the screenwriter on the project. Huston - always one to speak his mind, God bless him - had walked up to Muni at a party and called him a ‘shitty actor’. Now Muni was refusing to work on anything bearing his name. Warner Bros. brought in the novel’s author, W. R. Burnett, to rework the script with Huston and appease Muni. No dice. ‘It’s either him or me,’ declared Muni.

The studio told him to go take a hike.

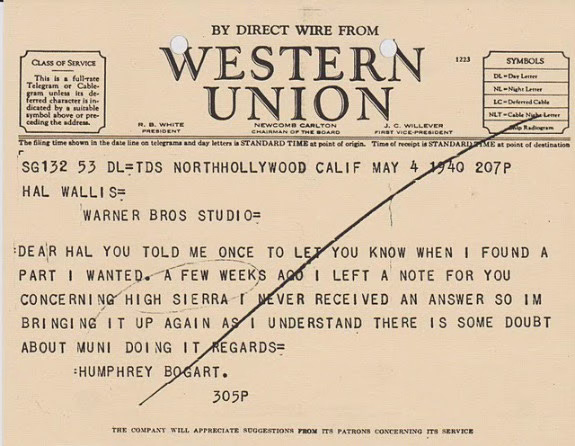

Bogart by this time had read the script and knew in his bones that this was his role. Learning Muni was no longer attached and that Raoul Walsh was going to direct, he began his campaign to land the part:

And Warner Bros. the dirty rats, offered the role to George Raft.

II “I wouldn’t give you two cents for a dame without a temper.”

We’re somewhere on Melrose, a bar with a good jukebox and no air-conditioning. It’s dark, rarely busy, kept afloat by industry folk who like the location and the shadows.

George Raft sits in a booth, tie undone. Not traditionally handsome, but fame fixed that; he looks like a movie star because he is one.

His friend, never late, already lighting his second cigarette, slides in opposite. Not a movie star, but a good actor. They’ve worked together before and like each other. He drops a dog-eared script on the table between them.

“George,” his friend says, “you don’t want this one.”

Drinks arrive. Raft sips his, weighing the angle.

“What makes you say that? I already said I’d do it.” Smiling a little at the lie he’s about to drop. “Besides, I could use the work.”

“Yeah, but you’ve done the work,” his pal says. “Same mug, same hat, same gun. You’ll get lost in it. And that ending? Aren’t you tired yet of dying for chumps.”

Raft leans back, squinting through the smoke. “Yeah, I wasn’t sure about the ending. I can get out of it. Nothing’s signed. You think they’ll find someone else? First Muni passes, now me.”

His friend shrugs. “Not really your problem, George. But they’ll find someone. Throw a shoe out the window and you’ll hit an actor hungry for this. But not you. You’ve paid your dues.”

A beat.

Raft laughs, low and genuine, pocketing the script. “If this acting thing doesn’t work out for you, Bogie, you should be my agent.”

“Yeah,” Bogart says, finishing his drink. “I may take you up on that.”

And maybe that’s how the part changed hands. Two pros playing each other. One stepping aside. The other finally stepping up.

Maybe.

All we know is that after talking it over with his buddy Humphrey Bogart, George Raft walked away from the role. A day or two later, Bogie signed on to play Roy Earle in HIGH SIERRA.

III “Look at the tag they hung on me? "Mad Dog" Earle, them newspaper rats!”

The film didn’t quite create Bogart the movie star, but it lit the fuse. Assured of top billing, every second of screen time declares Bogart has arrived at the top of his game, ready for the big time.

And then the studio blinked.

They bumped Ida Lupino, fresh from her breakout success alongside Raft and Bogart in THEY DRIVE BY NIGHT (1940) also directed by Walsh.

Bogart took it on the chin, but it would be the last time his name appeared second. From FALCON onwards it would now be his movie.

Roy Earle was loosely based on John Dillinger, still half-mythic in American memory. By 1941, the public’s tommy-gun fever was beginning to cool. HIGH SIERRA arrived as a kind of elegy, but still somehow feels older, lonelier, wider. I don’t think it’s a gangster movie at all.

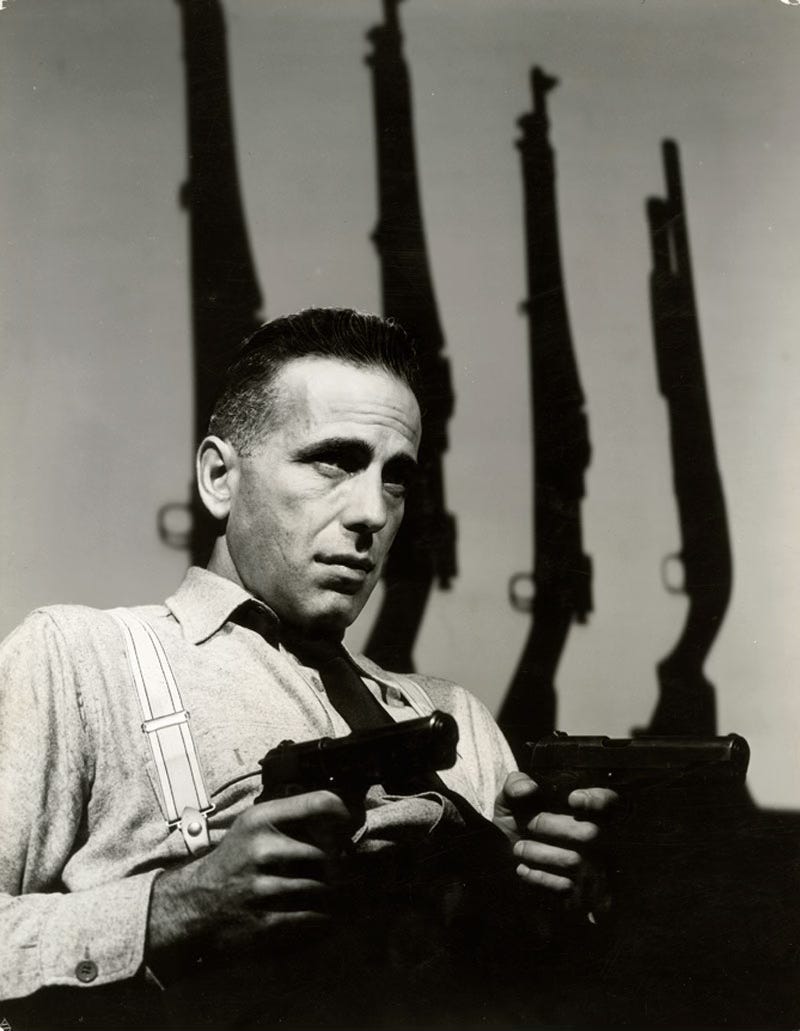

You sense the western influence in the first scenes: the open road, the long horizon, the promise of one last job away from civilisation, out in the mountains. Earle isn’t prowling city streets; he’s driving through dust. An outlaw sprung from prison carrying the weight of the Depression into a world that’s not prepared for his stock in trade; the Chicago typewriter:

The other characters are secondary to Earle, created to hone in on his character while they themselves are painted with wider brushstrokes. The dog he befriends, the regular girl he thinks he loves and the moll who loves him all bring to the surface a flaw: compassion.

And a longing for something else. Normality maybe. ‘Crashing out’ from one life to a hopefully better one is a recurring motif in the picture. Escape, not from jail, but from his life.

The heist itself is simple. A mountain-resort robbery, a crew of kids, a plan that unravels. But that’s what Roy is there for. He’s the pro. The only adult in the room. A weary cowboy saddled with greenhorns. Walsh stages it with the snap of a Warner crime picture: phones ringing, engines gunning, but can’t stop cutting to the mountains. The contrast is deliberate as that huge western sky threatens to swallow everything and everyone.

Bogart plays Earle better than Muni or Raft could have. Coiled silence. Understanding that stillness has power. You recognise this calm in McQueen’s Doc McCoy, De Niro’s Neil McCauley - men who measure their lives by exits and timing. The younger, inexperienced crew consider Earle the real deal. For Earle though, the calm and control he exudes isn’t bravado, it’s grace.

Bogart redefined the Hollywood tough guy persona. He takes no shit in THE MALTESE FALCON and is stoic as fuck in CASABLANCA, but here he’s also the most tender character in the film. His friendship with the dog Pard is famous and plays perhaps a tad over-sentimental to a modern audience. It doesn’t help that the dog is as ugly as sin, but maybe that’s the point.

Early on in the movie he pushes Lupino’s broken Marie away in favour of innocent farm girl, Velma, broken in a different way. Maybe a way he can fix. He uses the last of his money to pay for her operation, only to be rejected. Not because Velma discovers he’s an outlaw, but because she’s drawn to a shady character and his crowd back east - perhaps, ironically, the kind of man Earle was before prison.

It’s this doomed encounter that cracks him open. She represents redemption. Again its syrupy by modern standards, but Bogart makes it painful.

You can see him writing himself out of the story in his head. The one with the happy ending.

IV “All the A-1 guys are gone. Dead or in Alcatraz. If I only had four guys like you Roy... this knock-off would be a waltz.”

So he returns to a grateful Marie - and maybe she’s why you want all this to work out. While Earle may threaten to abandon both her and the mutt, it’s all talk. When he puts them on a bus and stays behind, he’s not ditching them… he’s saving them. And then it’s just him and the mountain.

When the job falls apart, it’s not alleyways but canyons he’s hunted through. It’s here that HIGH SIERRA drops the pretence of being a gangster picture completely. The final sequence of a lone outlaw on a mountain, gunfire echoing as the law closes in below belongs to the American West. When Marie cries as the credits loom, you may think it’s corny, but this is 1941 when Hollywood’s moral compass demanded that even its most loveable gangsters died at the hands of law and order, leaving the audiences with a reminder that crime, fun as fuck as it looks, never pays. Earle’s story flips that, using the same toolbox. Death, when it comes, isn’t a surrender to the powers that be. It’s a triumph.

Rewatching it again, I was struck by how much I wanted it all to work out for Earle. As a kid, I saw A FISTFUL OF DYNAMITE (1972) late one night with my dad, and by the credits I was crying my eyes out. Mike Senior, not one for sage wisdom, said this:

“If it still upsets you the next time you watch it, even though you know what’s coming, then it’s a great movie.”

Not a bad rule of thumb. And probably why it’s my favourite Sergio Leone movie.

There’s a moment in HIGH SIERRA where Bogart rails at the idea of the cops trying to pin a murder on him, and I felt the same disgust at the way he’s being vilified. Then remembered he had, in fact, killed the guy. You still want to give him a pass, because he’s trying to escape the man he was. And, anyway, that bastard had it coming.

Seen now, the film’s less about crime than about obsolescence. Roy’s professionalism, his sense of fairness, all the traits that made him good at his job no longer matter. The world’s moved on. Even simple folk like Velma are drawn elsewhere. America doesn’t need romantic outlaws anymore, it wants soldiers. Bogart’s gangster becomes a noir anti-hero, a cowboy outlaw, his getaway dashboard shifting to frontier desert.

There’s a reason Nicholas Ray and John Huston kept re-writing this movie in their own ways. You can trace a straight line from Roy Earle to REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE (1955) and THE ASPHALT JUNGLE (1950). BONNIE AND CLYDE (1967) too carries the ghost of Roy Earle - that blend of myth and melancholy, beauty and doom, blood and dust. I’ll go further and say that every heist film that ends with the crew scattered and the money meaningless owes a debt to HIGH SIERRA.

Maybe it was the first to admit that the score doesn’t matter. The getting away, or at least the attempt, is the story.

Raoul Walsh, a director often dismissed as just a workhorse next to auteurs like Ford, Hawks, Capra and Welles, finds poetry in that fatalism. His camera loves open space, the way it dwarfs men who believe they’re in control. He keeps returning to the road curling up into the mountains - a literal rise toward death - as if he knows he’s burying an entire genre on the summit.

After this, Bogart quits being a thug and becomes a philosopher with a revolver, a cynic with a conscience. More than that, the gangster picture grows up, shrugging off cheap thrills, its compass finally realigned. Still trigger-happy, but at least now asking why.

So yeah, this is technically a gangster film. It’s got the cops, robbers, a heist, bullets and dames. But watch it again and you’ll hear a phantom clink of spurs. By the time the credits roll, the question isn’t whether Roy Earle gets the money - it’s whether the world still has room for men like him.

And that’s why it’s a fucking western.

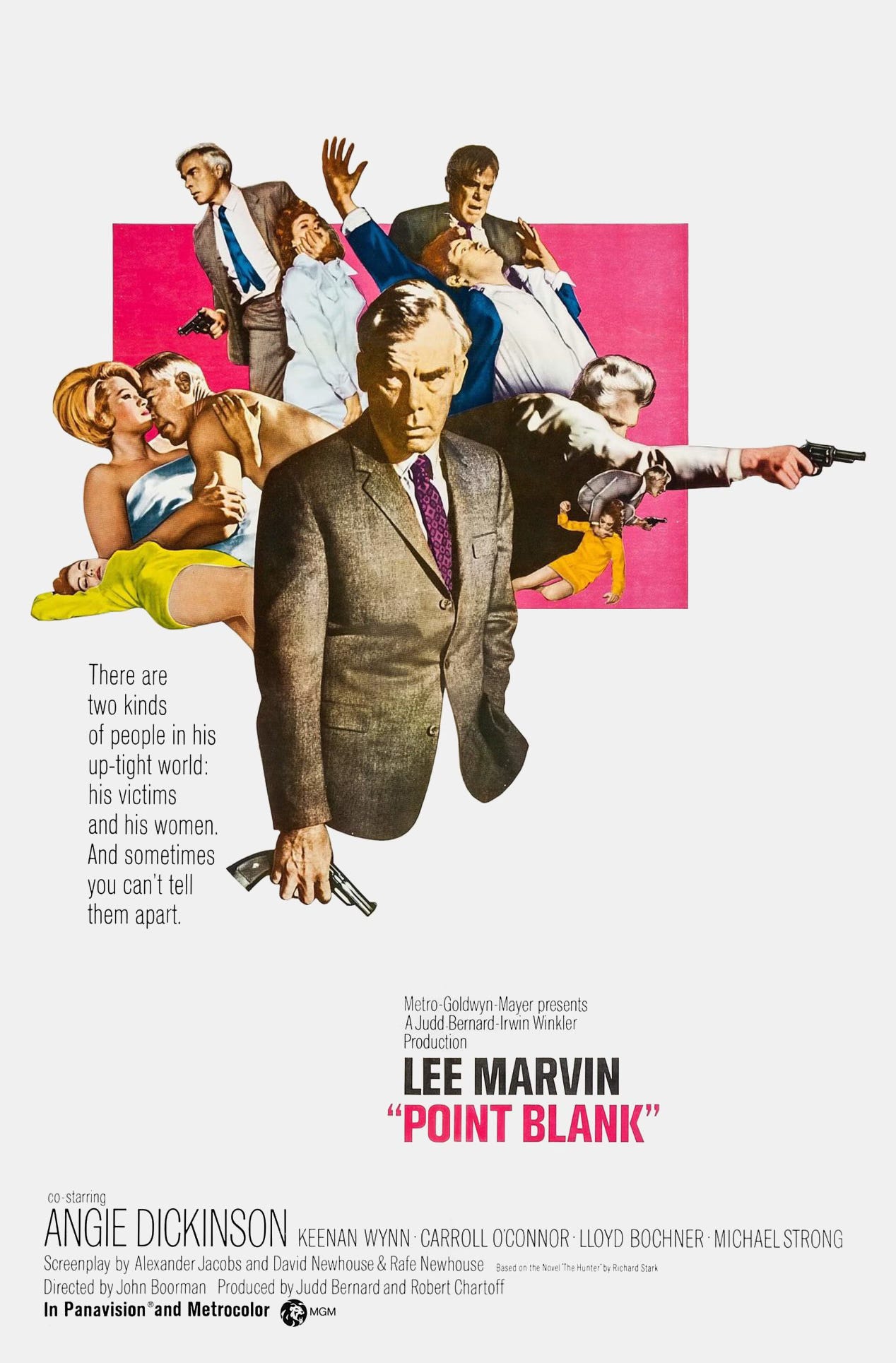

The Steal’s Poster of the Week

Want us to take a dive on a particular heist movie? Leave us a suggestion or two in the comments and feel free to let us know how we’re doing. We’d love to build THE STEAL around our readership, so come on board and help us course correct as we go.

Heist News

George Clooney dropped some more OCEAN’S 14 tidbits to Variety just before Christmas. Apparently the new instalment is “inspired by” GOING IN STYLE (1979) and Clooney has already enlisted his usual ratpack (Roberts, Damon, Pitt and Cheadle). They’re due to start shooting in October.

And in real world heist news: Fair play to the guy who helped lift more than €30 million worth of cash and jewels from a German bank vault… And still remembered to pay for parking.

Next Issue

Rob gets back on the London (great) train for Peter Weir’s BULLITT warm-up, ROBBERY(1967).

Thanks for reading. Thanks for subscribing. Thanks for sharing. Once the heat dies down we’ll see you at the prearranged location to split the take. What could possibly go wrong?